The rear-engined revolution: horses pushing the cart

Part 3: One engine is not enough

Author

- Mattijs Diepraam

Date

- October 7, 2005

Related articles

- A history of early post-war German F2, F Libre and sports cars - a stunning series of articles on the constructors that helped rebuild Germany's motorsport industry after World War II, by 'Uechtel'

- Part 3: The smaller marques

- Part 6: East German BMW specials

- Sokol 650 - Post-war Auto Union in disguise or a socialist F2 effort? Secrets of Tom Wheatcroft's "Type E" unveiled, by Jeroen Bruintjes/Holger Merten

- Part 1: To Moscow and back

- Part 2: Through the iron curtain

- Part 3: It's an Awtowelo!

- Part 4: Awtowelo debuts at Goodwood

- Bugatti T251 - Colombo's flawed brilliance, by Mattijs Diepraam/Eugene Zhmarin

- Connaught - Complex mind, complex output, by Felix Muelas/Mattijs Diepraam

- Cooper - Rear-ending in and out of Grand Prix racing, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas

- CTA-Arsenal - French pride rebuffed again!, by Mattijs Diepraam

- Early post-war German F2 cars - The BMW-derived specials that appeared in war-struck Germany, by Mattijs Diepraam

- 1947 Italian Championship - The race when Nuvolari waved the steering wheel at the crowd and a forgotten Championship, by Alessandro Silva

- 1955 British GP - Brabham's Cooper debuting among the all-conquering Mercs, by Felix Muelas/Gerald Swan

- 1958 Argentinian GP - The first GP win by a rear-engined car, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas

Click here to go back to part 2

If you have brakes slowing the car on all four corners, why not have power on all four wheels as well? That is the idea behind four-wheel drive. Some designers took that idea forward and created cars with separate engines powering each axle – although in the case of the Alfa Bimotore both engines were actually driving the rear wheels. The cars described in this final chapter pioneered the twin engine in the era when putting the engine – or at least one of them! – behind the driver was still far from usual practice.

Apart from the 1905 Christie Double-Ender the twin-engine concept wasn’t given much thought until the late 1920s. Walter Christie’s third car, also nicknamed ‘the blue flyer’, carried two transversely mounted 4-cylinder engines, the front one of a whopping 13,803cc capacity producing 60hp, the rear one of 6435cc giving 30hp – although the overall power was reported to be 120hp. A speed-record car, it set 152.4kph on Cape May Beach, New Jersey, on September 6, 1905. Then Ettore Bugatti conceived a 16-cylinder aero engine during the Great War, a design that was taken up by Duesenberg, before he unearthed the concept in 1928, mating two straight-eight blocks of 1900cc capacity.

This sparked a whole range of multi-cylinder double-engine concepts. Maserati debuted its ‘Sedici Cilindri’, confusingly named V4, later followed up by the larger V5. Over on the other side of the Atlantic, Leo Goossen created a similar double-eight unit of two Miller 91 engines to power the Sampson Special. And countering Maserati’s V4 was Vittorio Jano’s 1931 Tipo A, that used two 1750cc straight-sixes to create a 3.5-litre ensemble.

However, all of these ‘double’ engines were in fact two engines mounted side-by-side to become one larger engine. The veteran Christie car’s concept wasn’t re-created until Scuderia Ferrari technical director Luigi Bazzi came up with the idea of the Bimotore.

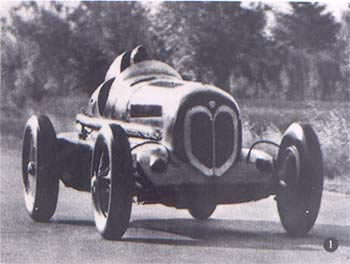

Alfa Romeo Bimotore

Works Alfa Romeo involvement in Grand Prix racing ceased in 1933, the clover-leaf marque handing over responsibility to Scuderia Ferrari. Enzo’s private squad valiantly defended Italian honours against the rapidly growing might of the two German manufacturers but with nothing much coming out of the Portello factory in terms of new developments, especially with regard to the new 750kg formula, the prancing horse’s engineering staff started work on projects of their own.

Luigi Bazzi, the Scuderia’s technical director, came up with a plan to tackle the big-prize Italian Libre events at the start of the 1935 season with a car that would simply out-power the 750kg German Grand Prix machines. To do this economically, an existing chassis and engine – or rather, engines – would be needed as a starting point. Bazzi figured that the Tipo B ‘P3’ chassis would be suitable enough for the double-engine trickery. In an effort to step away from the mating difficulties experienced with the Tipo A double-six he proposed that the two engines would be completely separate and, for better weight distribution, placed at either end of the car. Remarkably, this didn’t imply the perhaps obvious decision for four-wheel drive. Instead, Bazzi wanted to have the engines power the rear wheels only.

The work involved to retain rear-wheel drive reshaped the entire Tipo B rear end. As the rear engine would be in the way of the Tipo B's beam-axle rear suspension layout, this was thrown out completely in favour of a wishbone configuration, matched with leaf springs. The rear engine was then turned around with its drive pointing towards the front. A hollow gearbox main-shaft led to the clutch centre where rear drive and front drive met. Rear power could be temporarily disengaged through a simple dog clutch. With the rear engine taken the place of the fuel tank, pannier tanks were placed at the sides, containing even more weight within the car's wheelbase.

The work involved to retain rear-wheel drive reshaped the entire Tipo B rear end. As the rear engine would be in the way of the Tipo B's beam-axle rear suspension layout, this was thrown out completely in favour of a wishbone configuration, matched with leaf springs. The rear engine was then turned around with its drive pointing towards the front. A hollow gearbox main-shaft led to the clutch centre where rear drive and front drive met. Rear power could be temporarily disengaged through a simple dog clutch. With the rear engine taken the place of the fuel tank, pannier tanks were placed at the sides, containing even more weight within the car's wheelbase.

Two cars were completed for the design's premiere in the Tripoli GP. The first was using the new 3.2-litre supercharged Grand Prix engines, together giving 540hp at 5400rpm, while the other took the proven 2.9-litre units which gave a total of 520hp at the same rev count. The smaller-engined car was finished first and was tested by Attilio Marinoni and Tazio Nuvolari on a closed section of the Brescia-Bergamo autostrada on 10 April 1935. Nuvolari eventually recorded a phenomenal top speed of 210mph.

At Mellaha, the choice of two engines powering the rear wheels while one of the engines sat on top of them showed that the concept gave excellent traction - but as long as the tyres lasted! In all, Nuvolari had to pit eight times for new tyres while Chiron in the smaller car came in six times. The cars proved to be extremely fast as they thundered down the straights of Mellaha but their weight cost them in the corners, and it ate their tyres too. Nuvolari finished fourth, with Chiron one place behind, trailing the German cars by quite a margin.

Two weeks later, at AVUS, tyres were again a concern. In fact, they were more of a hazard as Nuvolari saw the treads flying off as he hammered down the Berlin speedway. As Nuvolari didn't let this stop him from going balls-out, forcing him to pit as early as on lap 2 during his qualifying heat, Chiron took a more circumspect approach. He first caressed his car into the final by taking fourth in his heat, and then delicately eased it across the line in second place, although one rear tyre was already down to the canvas… While this was hardly a race tactic that could be persuaded upon the Flying Mantuan, Chiron's calmly paced run did bring the Scuderia the prize money it was looking for.

With the Grand Prix season getting underway, the Libre cars were now redirected towards record-breaking attempts. The target was Hans Stuck's Class C flying-mile record set in his Auto Union on the Lucca-Altopascio autostrada, and Ferrari went to the same stretch of road trying to better that. They would not break the 3.5-litre Class C record itself as the Bimotori were Class B cars but Stuck's 199mph would be the figure to beat. Nuvolari would be the main driver, Pintacuda the relief man. Although Nuvolari had to wrestle to keep the car straight under vicious cross-winds he still brought the Class B record to 200.77mph, in the process beating the Auto Union average. The flying-kilometre record was set at 199.92mph, which was also outstripping Caracciola's Mercedes record set in Hungary. A speed trap had recorded a top speed of nearly 209mph.

This was the end of the Bimotori's first life. The big-engine car was subsequently scrapped while Chiron's car was sold to British amateur Austin Dobson in 1937. After a single season Dobson sold the car on to Peter Aitken, who quickly turned the car into a 'Monomotore', cutting it in half, removing the rear engine, along with the transmission and suspension, and replacing it with an ENV pre-selector gearbox and a new back axle. Completed in 1939, the so-called Alfa-Aitken only ran a couple of times before it was mothballed during the war.

Post-war it came into the hands of RV Wallington who famously used the car to win the first British post-war race meeting at Gransden Lodge. Wallington then sold it to Major Tony Rolt, one of the Colditz heroes, who had it further modified by later 4WD guru Freddie Dixon. The adaptations included replacing the superchargers with eight SU carburettors and enlarging the engine capacity to 3.4 litres. This made it eligible as a Grand Prix car, and as such it was run in several events in the late forties, its high point being the inaugural Zandvoort GP of 1948, in which Rolt finished a close second to Prince Bira's 4CL. The 'Monomotore' eventually found its way to New Zealand.

Fuzzi-JAP

One of strangest names in the history of racing car manufacturing is hiding one of the most oddly shaped creatures ever to come out of it. As much as it looked unlikely to be fast, it happened to be able to torment Shelsley Walsh's hillclimb in just over 44 seconds. The vehicle was conceived in 1935 by free-thinking British engineer Robert Waddy, who christened his double-engined monster 'Fuzzi'. The name hailed after the aircraft fusilage that inspired Waddy to create a chrome-molybdenum tubed car based on the same lay-out as an Avro Avian light airplane. Basically one of the earliest spaceframe cars ever built, it followed the same multi-tubular principle as Auguste Monaco's outrageous Trossi-Monaco with its radial engine.

The double-engine innovation came about thanks to Waddy mounting a two-stroke 500cc JAP engine above either axle of the car, each using its own Rudge gearbox (later replaced by Morgan Aero units) and chain drive to power a set of wheels. Even more adventurously, the engines were controlled by an ingenious throttle pedal that could be used to accelerate both engines or either one of them. By pressing the device flat down the two JAPs would scream simultaneously, and by flicking his heel and toes back and forth he could make quick in-corner adjustments by taking throttle away from either the front or the rear unit. It was a unique four-wheel drive concept that was never seen again.

The acceleration powers of 'Fuzzi' were staggering during its sprint outings between 1936 and 1939. The standing-start half-mile was completed in under 26 seconds. Waddy rebuilt it after the war, replacing the twin engines with a single big-block Mercury V8, but couldn't repeat the results of the original concept.

Fageol Twin Coach Special

The American continent saw its second implementation of the twin-engined lay-out in the immediate aftermath of World War II, and in its own way it was just as exciting as the first. Lou Fageol's entry to the 1946 Indianapolis 500 was a strange creature indeed, based as it was on Harry Miller's ill-fated 1935 front-wheel drive Ford adventure. The drive systems of these 11-year-old machines were combined with small-block Offenhauser engines and placed at either end of the car's chassis, creating a four-wheel drive Indy racer.

Fageol was the manufacturer of the Fageol Twin Coach bus - also carrying twin engines! - and thus named the car the Fageol Twin Coach Special. The 1.59-litre Offy engines came from midget racing but their stroke was decreased to give a capacity of 1.47 litres. Combined they remained eligible for the supercharged capacity rules of the time, and so the engines were blown in European fashion using Roots superchargers, which were less peaky than the American centrifugal superchargers. The two engines shared a throttle linkage but could be split and disconnected.

Fageol was the manufacturer of the Fageol Twin Coach bus - also carrying twin engines! - and thus named the car the Fageol Twin Coach Special. The 1.59-litre Offy engines came from midget racing but their stroke was decreased to give a capacity of 1.47 litres. Combined they remained eligible for the supercharged capacity rules of the time, and so the engines were blown in European fashion using Roots superchargers, which were less peaky than the American centrifugal superchargers. The two engines shared a throttle linkage but could be split and disconnected.

Although it outweighed the competition, the Twin Coach concept centered around the perfect traction, gained by four-wheel drive and perfect weight distribution. The theory was validated by practice when Paul Russo qualified on the front row of the grid, taking second place with an average of 126.183mph. Russo raved about the car's stability, as did its designer Paul Weirick and Lou Fageol himself, who both did practice laps in the car.

It was less lucky in the race, however, perhaps having taken over some of the Miller luck. Running near the front on lap 16 Russo hit a patch of oil possibly left behind by an Alfa Romeo and slid into the wall. He was carried away with a broken leg, and the Fageol Twin Coach Special wasn't seen again.

DB-Panhard

Having started in 1938 creating Citroën-engined barchettas, Frenchmen Charles Deutsch and René Bonnet continued to be special builders in the immediate post-war era, and found out that the Dyna Panhard and its Panhard flat-twin engine best suited their need for a cheap and small sports car. Air-cooled like the JAP engine used in the 'Fuzzi', the Panhard engine was linked to a front-wheel drive transmission, which helped to create the nimble DB-Panhard sports car used successfully well into the fifties.

The Panhard engine - or in fact two of them - also formed the basis of an exciting F2 project started in 1951. Well inside the formula's 2-litre capacity DB simply put one 750cc Panhard engine and transmission system at either end by cutting and shutting two front ends of their 500cc frames. This created a twin-engined four-wheel drive machine with one lever operating the two gearboxes. The car was tested in the autumn, with plans to increase the engines' capacity to 850cc each and a projected total output of 120hp. The updated version never appeared.

Since then we haven't seen anything close to a successful twin-engine implementation ever again. Four-wheel drive, however, continued to gain momentum until it boomed in F1 in 1969. In that sunny season that failed to produce a rain race it was quickly put aside again, perhaps too quickly, and developments ground to a halt until Audi revived them to revolutionise rallying. Another revolution - the mid-engined racing car - put an end to the concept of using two engines to further improve weight distribution.

More than one engine... today

But it might be coming back, and doubly so, in the shape of fuel-cell-powered electric engines each driving a single wheel! The Mitsubishi Lancer Evo IX MIEV is an experimental rally car that recently made its debut in the Japanese Shikoku EV Rally of 2005. This extraordinary Lancer Evo will be Mitsubishi's second MIEV test vehicle, following the Colt EV that was announced in May 2005. The MIEV core technology is a new in-wheel motor that uses a hollow doughnut construction to locate the rotor outside the stator. This is the opposite of a common electric motor where the rotor turns inside the stator. The concept not only lowers the unsprung weight, which would always have been a handicap when trying to mount an engine inside a wheel. It also makes more efficient use of the cramped space to provide room for the brakes. And last but not least the outside rotor makes the front wheels suitable for steering, which is pretty beneficial if you want to create a four-wheel drive in-wheel motor rally vehicle.

Each rotor produces a power output of 68hp, thus giving a massive combined output of 272hp, easily above what the combustion-engined Evo produces. And that's wheel power, not flywheel power, since the transmission losses are non-existent! Torque figures are even more shattering - 518 Nm at 1500rpm. The only thing keeping the MIEV from really taking on its flame-belching brother is its massive curb weight of 1590kgs, no doubt caused by the 24 Lithion-ion batteries scattered all over the car's floorpan.

Each rotor produces a power output of 68hp, thus giving a massive combined output of 272hp, easily above what the combustion-engined Evo produces. And that's wheel power, not flywheel power, since the transmission losses are non-existent! Torque figures are even more shattering - 518 Nm at 1500rpm. The only thing keeping the MIEV from really taking on its flame-belching brother is its massive curb weight of 1590kgs, no doubt caused by the 24 Lithion-ion batteries scattered all over the car's floorpan.

Will this be the future of car manufacturing and, indeed, motor racing? There is no doubt about it. We can only hope that the new generation of cars will have DVD players delighting the driver with the best Ferrari, Matra and Honda sounds that have been recorded and saved for posterity…